-

SOFTWARE

SOFTWARE HCM Productivity Suite Query Manager Query Manager Add-ons Document Builder Payroll Pack Variance Monitor DSM for HCM GeoClock

-

SERVICES

SERVICES PRISM for HR & Payroll SAP SuccessFactors Integration monitoring Payroll reporting Report writing Custom development SAP BTP

- All Solutions

- Request Estimate

-

Resources

Resources Blogs Read the latest updates on SAP SLO, SAP HCM, Data & Privacy, and Cloud Events and Webinars Discover all our events and webinars from around the world Video library Watch videos and improve your SAP knowledge

- About

CCPA: The Ultimate Guide for SAP Systems

Disclaimer

This guide is not intended as legal advice and should not be construed as such. Its purpose is to provide information for educational purposes only and makes no claims or guarantees with regards to efficacy, accuracy or full compliance with the law discussed herein.

Please consult with an appropriate legal advisor before implementing any part of a CCPA compliance project. EPI-USE Labs will not take any responsibility for misinterpretation or incorrect application of practical measures towards compliance resulting from the use of this guide.

There is a global wave of data privacy legislation that affects the way in which companies do business. We can all agree that having control over our private data is important from an individual’s perspective, but with decades of freedom in using personal data, businesses are now forced to rethink their approach, and sometimes even their business models. In many cases, personal data used to be considered an asset, but has now become a liability or a toxic asset.

This guide is designed to provide you with insight and practical tips on compliance with the California Consumer Privacy Act, or the CCPA as we will refer to it throughout. We are not your lawyers (see our disclaimer), and as every system is unique, we cannot guarantee that you will be compliant after following this guide. But what we aim to achieve is that you will have a deeper understanding of the law and the way it compares to GDPR. We have also suggested a number of practical actions you can take towards compliance.

About the California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA)

The California Consumer Privacy Act, or CCPA, is a bill that enhances privacy rights and consumer protection for residents of California in the United States. It provides Californian consumers with several rights regarding their personal information. In broad terms, the law does the following:

- It gives Californian residents, referred to as ‘consumers’, the right to know what information is being collected on them, both on and offline.

- It gives Californian consumers the right to know whether their information is being sold or shared, as well as with whom.

- It gives the consumers a right and practical means to stop the sale of their personal information.

- It gives consumers the right to request the deletion of their personal data (with some exceptions).

- It prohibits preferential treatment of consumers who willingly share their data, as opposed to those who opted out or made alternative choices regarding their personal data.

In this guide we explore this further, including applying the law to specific phases of a typical data privacy compliance project.

DOWNLOAD CCPA: THE ULTIMATE GUIDE FOR SAP SYSTEMSIt isn’t the same thing

Let’s get this out of the way: GDPR compliance does not equal CCPA compliance. There are some similarities between the two laws, but the CCPA has a different focus to GDPR, making compliance different in most respects. This chapter gives a quick overview of the key differences between the two laws.

Comparing CCPA with GDPR

| CCPA | GDPR | |

|---|---|---|

| Who must comply? | CCPA For-profit entities that engage Californian consumers and households. |

GDPR Processors and Controllers that interact with EU Citizens. |

| Who is protected? | CCPA ‘Consumers’ who are natural persons and California residents. |

GDPR Identifiable natural persons who are EU nationals or residents. |

| What is protected? | CCPA Personal information, broadly defined to include any identifier that can be linked to a consumer. |

GDPR Personal information that can be used to identify a natural person. |

| How are they protected? | CCPA Consumers can opt out of the sale of their personal data. There are penalties for breaches. A broader definition of “consumer” makes anonymization far more challenging. |

GDPR Data subjects must opt into the processing of their data. Clear security directives. A narrower definition of data subject makes anonymization of personal data simpler. |

| What are the consequences of non-compliance? | CCPA Penalties of up to $7500 per violation. |

GDPR Penalties of 4% of annual global revenue or €20m, whichever is higher. |

Who must comply?

The CCPA requires any entity defined as a ‘business’ that has any activities related to ‘consumers’ within the borders of California to comply, given three specific thresholds (see Chapter 2). Similar to GDPR, this applies regardless of physical location.

The GDPR is broader than the CCPA as it includes any person or entity that engages EU residents, regardless of their physical location, and is not limited to businesses.

Who is protected?

The CCPA protects ‘consumers’ who are defined as California residents. This will include employees* and customers, so even if you are a B2B company, you will need to comply.

GDPR protects ‘data subjects’ that are natural persons who are EU residents, identifiable, and to which the personal data that you collect relates.

* Amendment AB25, aimed at restricting the way in which employee data is managed under the CCPA, will provide limited rights to employees as consumers. Regardless of these possible future restrictions, employee data is still subject to compliance.

What is protected?

For both the CCPA and GDPR, ‘personal information’ is protected. The CCPA has a broader definition of what that means, specifically including any information that can be linked to a person, up to household or device level. The implication is that data like IP addresses is included as ‘personal information’ for the purposes of the CCPA.

GDPR focuses purely on information that will allow you to identify a given person directly, and includes a number of special categories of data that are prohibited from processing.

How are they protected?

The CCPA puts the emphasis on the sale of personal information, giving consumers the right to opt out of having their data sold (which is also broadly defined; see Chapter 4). There are penalties for data breaches, although there aren’t any explicit data security requirements. As a consequence of the way in which personal information is defined, anonymization is much more complicated to achieve.

GDPR is explicit about the extent to which data controllers and processors need to secure their systems as well as implement appropriate organizational measures to protect personal data. Different from the CCPA that provides the right to opt out, GDPR requires specific and informed opt-in to the different ways that personal data is used.

What happens when you don’t comply?

When it comes to a private right of action (private individuals suing the organization in breach), both GDPR and the CCPA provide avenues. The CCPA is generally more prescriptive as to the monetary value that can be claimed in civil cases for statutory damages ($100 to $750 per violation). GDPR is not prescriptive in this sense.

Beyond civil cases, there are also administrative or civil penalties to consider. The CCPA gives the Attorney General the power to penalize an offender with $2 500 per violation, or up to $7 500 per violation if it was intentional. When violations are noted, offenders get 30 days to fix the issue before any actions take place.

GDPR also contains heavy administrative fines of 4% of company turnover or €20 million, whichever is higher.

A few of us won’t have to. (But just a few).

The good news is that not everybody has to comply with the new CCPA law. The bad news is that there are very few companies that will be so lucky. In this chapter, we look at who needs to comply with the CCPA and give you a simple-to-follow flowchart to determine whether you need to do so.

California Civil Code 1798.140:

(1) A sole proprietorship, partnership, limited liability company, corporation, association, or other legal entity that is organized or operated for the profit or financial benefit of its shareholders or other owners, that collects consumers’ personal information, or on the behalf of which such information is collected and that alone, or jointly with others, determines the purposes and means of the processing of consumers’ personal information, that does business in the State of California…

(2) Any entity that controls or is controlled by a business, as defined in paragraph (1), and that shares common branding with the business. “Control” or “controlled” means ownership of, or the power to vote, more than 50 percent of the outstanding shares of any class of voting security of a business; control in any manner over the election of a majority of the directors, or of individuals exercising similar functions; or the power to exercise a controlling influence over the management of a company. “Common branding” means a shared name, servicemark, or trademark.

California Civil Code 1798.145:

(a) The obligations imposed on businesses by this title shall not restrict a business’s ability to:

(1) Comply with federal, state, or local laws.

(2) Comply with a civil, criminal, or regulatory inquiry, investigation, subpoena, or summons by federal, state, or local authorities.

(3) Cooperate with law enforcement agencies concerning conduct or activity that the business, service provider, or third party reasonably and in good faith believes may violate federal, state, or local law.

(4) Exercise or defend legal claims.

(5) Collect, use, retain, sell, or disclose consumer information that is deidentified or in the aggregate consumer information.

(6) Collect or sell a consumer’s personal information if every aspect of that commercial conduct takes place wholly outside of California. For purposes of this title, commercial conduct takes place wholly outside of California if the business collected that information while the consumer was outside of California, no part of the sale of the consumer’s personal information occurred in California, and no personal information collected while the consumer was in California is sold. This paragraph shall not permit a business from storing, including on a device, personal information about a consumer when the consumer is in California and then collecting that personal information when the consumer and stored personal information is outside of California.

(b) The obligations imposed on businesses by Sections 1798.110 to 1798.135, inclusive, shall not apply where compliance by the business with the title would violate an evidentiary privilege under California law and shall not prevent a business from providing the personal information of a consumer to a person covered by an evidentiary privilege under California law as part of a privileged communication.

(c) (1) This title shall not apply to any of the following:

(A) Medical information governed by the Confidentiality of Medical Information Act (Part 2.6 (commencing with Section 56) of Division 1) or protected health information that is collected by a covered entity or business associate governed by the privacy, security, and breach notification rules issued by the United States Department of Health and Human Services, Parts 160 and 164 of Title 45 of the Code of Federal Regulations, established pursuant to the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (Public Law 104-191) and the Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health Act (Public Law 111-5).

(B) A provider of health care governed by the Confidentiality of Medical Information Act (Part 2.6 (commencing with Section 56) of Division 1) or a covered entity governed by the privacy, security, and breach notification rules issued by the United States Department of Health and Human Services, Parts 160 and 164 of Title 45 of the Code of Federal Regulations, established pursuant to the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (Public Law 104-191), to the extent the provider or covered entity maintains patient information in the same manner as medical information or protected health information as described in subparagraph (A) of this section.

(C) Information collected as part of a clinical trial subject to the Federal Policy for the Protection of Human Subjects, also known as the Common Rule, pursuant to good clinical practice guidelines issued by the International Council for Harmonisation or pursuant to human subject protection requirements of the United States Food and Drug Administration.

(2) For purposes of this subdivision, the definitions of “medical information” and “provider of health care” in Section 56.05 shall apply and the definitions of “business associate,” “covered entity,” and “protected health information” in Section 160.103 of Title 45 of the Code of Federal Regulations shall apply.

(d) This title shall not apply to the sale of personal information to or from a consumer reporting agency if that information is to be reported in, or used to generate, a consumer report as defined by subdivision (d) of Section 1681a of Title 15 of the United States Code, and use of that information is limited by the federal Fair Credit Reporting Act (15 U.S.C. Sec. 1681 et seq.).

(e) This title shall not apply to personal information collected, processed, sold, or disclosed pursuant to the federal Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act (Public Law 106-102), and implementing regulations, or the California Financial Information Privacy Act (Division 1.4 (commencing with Section 4050) of the Financial Code). This subdivision shall not apply to Section 1798.150.

(f) This title shall not apply to personal information collected, processed, sold, or disclosed pursuant to the Driver’s Privacy Protection Act of 1994 (18 U.S.C. Sec. 2721 et seq.). This subdivision shall not apply to Section 1798.150.

(g) Notwithstanding a business’s obligations to respond to and honor consumer rights requests pursuant to this title:

(1) A time period for a business to respond to any verified consumer request may be extended by up to 90 additional days where necessary, taking into account the complexity and number of the requests. The business shall inform the consumer of any such extension within 45 days of receipt of the request, together with the reasons for the delay.

(2) If the business does not take action on the request of the consumer, the business shall inform the consumer, without delay and at the latest within the time period permitted of response by this section, of the reasons for not taking action and any rights the consumer may have to appeal the decision to the business.

(3) If requests from a consumer are manifestly unfounded or excessive, in particular because of their repetitive character, a business may either charge a reasonable fee, taking into account the administrative costs of providing the information or communication or taking the action requested, or refuse to act on the request and notify the consumer of the reason for refusing the request. The business shall bear the burden of demonstrating that any verified consumer request is manifestly unfounded or excessive.

(h) A business that discloses personal information to a service provider shall not be liable under this title if the service provider receiving the personal information uses it in violation of the restrictions set forth in the title, provided that, at the time of disclosing the personal information, the business does not have actual knowledge, or reason to believe, that the service provider intends to commit such a violation. A service provider shall likewise not be liable under this title for the obligations of a business for which it provides services as set forth in this title.

(i) This title shall not be construed to require a business to reidentify or otherwise link information that is not maintained in a manner that would be considered personal information.

(j) The rights afforded to consumers and the obligations imposed on the business in this title shall not adversely affect the rights and freedoms of other consumers.

(k) The rights afforded to consumers and the obligations imposed on any business under this title shall not apply to the extent that they infringe on the noncommercial activities of a person or entity described in subdivision (b) of Section 2 of Article I of the California Constitution.

(Amended (as added by Stats. 2018, Ch. 55, Sec. 3) by Stats. 2018, Ch. 735, Sec. 10. (SB 1121) Effective September 23, 2018. Section operative January 1, 2020, pursuant to Section 1798.198.)

1798.150. (a) (1) Any consumer whose nonencrypted or nonredacted personal information, as defined in subparagraph (A) of paragraph (1) of subdivision (d) of Section 1798.81.5, is subject to an unauthorized access and exfiltration, theft, or disclosure as a result of the business’s violation of the duty to implement and maintain reasonable security procedures and practices appropriate to the nature of the information to protect the personal information may institute a civil action for any of the following:

(A) To recover damages in an amount not less than one hundred dollars ($100) and not greater than seven hundred and fifty ($750) per consumer per incident or actual damages, whichever is greater.

(B) Injunctive or declaratory relief.

(C) Any other relief the court deems proper.

(2) In assessing the amount of statutory damages, the court shall consider any one or more of the relevant circumstances presented by any of the parties to the case, including, but not limited to, the nature and seriousness of the misconduct, the number of violations, the persistence of the misconduct, the length of time over which the misconduct occurred, the willfulness of the defendant’s misconduct, and the defendant’s assets, liabilities, and net worth.

(b) Actions pursuant to this section may be brought by a consumer if, prior to initiating any action against a business for statutory damages on an individual or class-wide basis, a consumer provides a business 30 days’ written notice identifying the specific provisions of this title the consumer alleges have been or are being violated. In the event a cure is possible, if within the 30 days the business actually cures the noticed violation and provides the consumer an express written statement that the violations have been cured and that no further violations shall occur, no action for individual statutory damages or class-wide statutory damages may be initiated against the business. No notice shall be required prior to an individual consumer initiating an action solely for actual pecuniary damages suffered as a result of the alleged violations of this title. If a business continues to violate this title in breach of the express written statement provided to the consumer under this section, the consumer may initiate an action against the business to enforce the written statement and may pursue statutory damages for each breach of the express written statement, as well as any other violation of the title that postdates the written statement.

(c) The cause of action established by this section shall apply only to violations as defined in subdivision (a) and shall not be based on violations of any other section of this title. Nothing in this title shall be interpreted to serve as the basis for a private right of action under any other law. This shall not be construed to relieve any party from any duties or obligations imposed under other law or the United States or California Constitution.

(Amended (as added by Stats. 2018, Ch. 55, Sec. 3) by Stats. 2018, Ch. 735, Sec. 11. (SB 1121) Effective September 23, 2018. Section operative January 1, 2020, pursuant to Section 1798.198.)

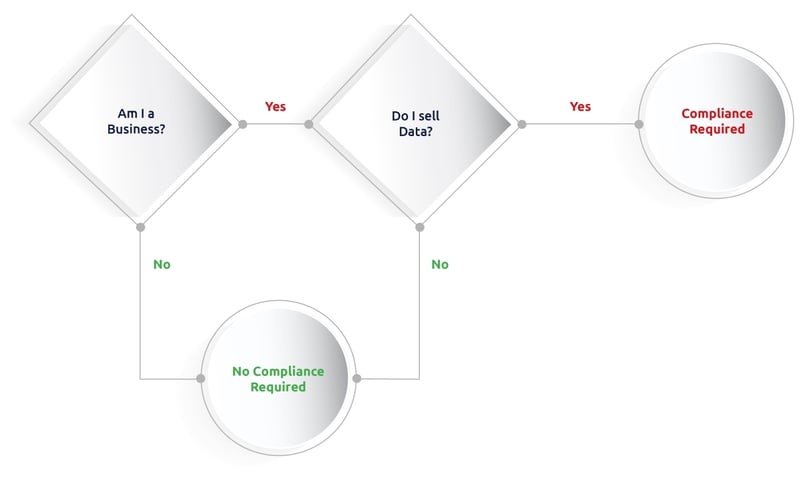

Being a business and selling data

Compliance with the CCPA boils down to two questions, namely:

- Is my operation regarded as a business with activities in California?

- And do my revenue-generating activities include the use of personal data of consumers?

Of course, if you are using personal data to generate revenue, you automatically qualify as a business, which means that it is likely that you are required to comply.

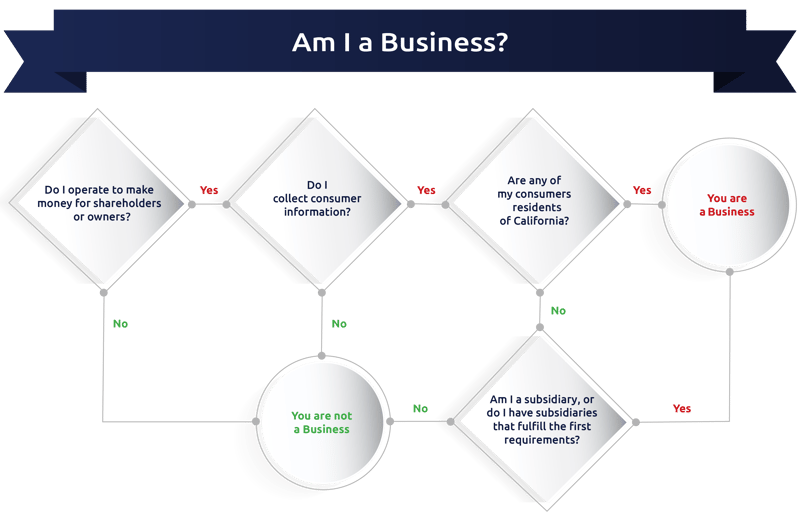

1. Is my operation a business?

In California Civil Code 1798.140, we learn that you are a business if

a) you operate with the aim to generate profits,

b) require personal data as part of your operations, and

c) have any business activity in California.

The implication is that your physical presence is irrelevant; the moment you collect personal information from any Californian resident as part of doing any form of profit-making activity, you are regarded as a business.

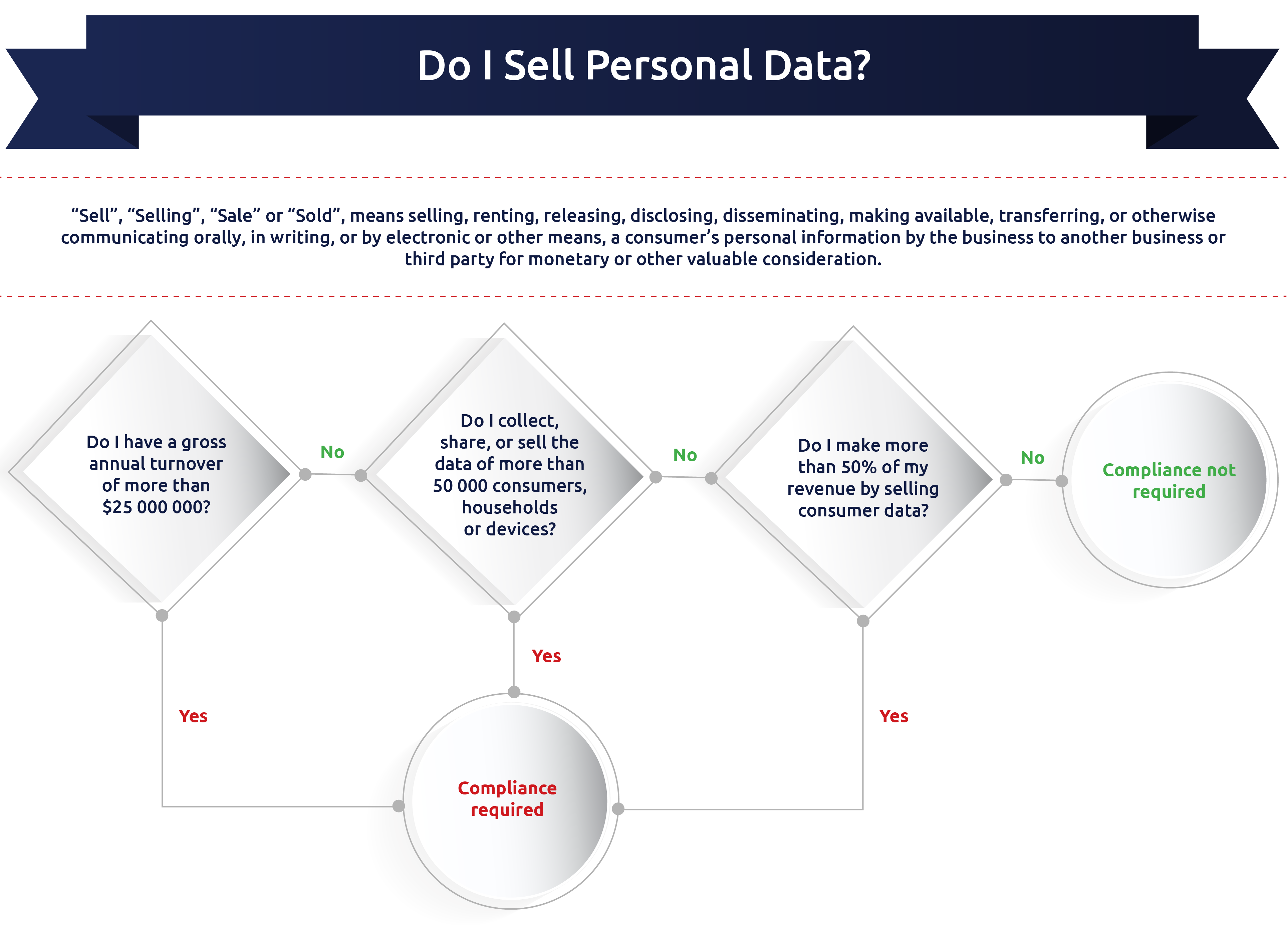

2. Do my revenue-generating activities include the use of personal data of consumers?

The CCPA does provide some leeway by adding certain thresholds that would qualify a business for compliance in 1798.140(c)(1):

(A) Has annual gross revenues in excess of twenty-five million dollars ($25,000,000), as adjusted pursuant to paragraph (5) of subdivision (a) of Section 1798.185.

(B) Alone or in combination, annually buys, receives for the business’s commercial purposes, sells, or shares for commercial purposes, alone or in combination, the personal information of 50,000 or more consumers, households, or devices.

(C) Derives 50 percent or more of its annual revenues from selling consumers’ personal information.

Don’t get too excited about these thresholds though. The CCPA uses a broad definition of ‘personal information’.

What is considered personal information?

In 1798.1409(o)(1) we learn that:

Personal information means information that identifies, relates to, describes, is capable of being associated with, or could reasonably be linked, directly or indirectly, with a particular consumer or household.

Are you collecting IP addresses for web analytics? Are you using cookies? Does the information you collect link not just to individuals, but perhaps to households or even single devices? Even though a 50 000 consumer threshold looks like a lot, it only takes 137 unique visitors from California to your website per day to fill up that quota and relates to any identifiers that can link back to a consumer or household.

Then there are the profits on the sales of this information, which is more specific to data brokers who make money by selling personal data. If you earned $100 this year, and $50 of that was generated by selling consumers’ data, you will have to comply.

But even ‘selling’ here isn’t a simple concept.

According to Code 1798.140(t)(1):

‘Sell’, ‘selling’, ‘sale’ or ‘sold’ means selling, renting, releasing, disclosing, disseminating, making available, transferring, or otherwise communicating orally, in writing, or by electronic or other means, a consumer’s personal information by the business to another business or a third party for monetary or other valuable consideration.

So, who won’t have to comply?

Code 1798.145 provides some exceptions for compliance, most notably when a business’ activities take place ‘wholly outside of California’ and does not process any personal information of a California resident.

The challenge here, specifically to businesses that operate on the Internet, is to know whether or not a visitor is from California. But if you are running a fish tackle shop in Arkansas where no Californians ever have, or ever will, set foot, and you operate without a website, and don’t collect any personal information, then it is likely that you are not required to comply.

Other exceptions noted in this Code relate mostly to organizations that collect medical and other forms of sensitive personal information, which are already subject to specific privacy laws for their particular contexts.

Broadly speaking...

One might say that the devil is in the details, but in the case of the CCPA the devil is really in the broad definitions. Some businesses may want to find a way to avoid the burden of compliance, but with a number of other similar laws developing in other states, as well as across the globe, it is a safer approach to ensure compliance.

It gets complicated really fast

Compliance projects can get complicated. It requires time and dedication from specific team members across different departments, including legal/compliance, business owners and IT. Due to imminent deadlines for implementation, it typically runs over shorter periods of time.

Managing a complex, high-pressure project is a challenge, and like any challenge, it begins with proper planning. In this chapter, we provide a few tips on planning for your CCPA compliance project.

You can only change what you know

A CCPA compliance project plan broadly consists of four stages, namely:

- Scope & Plan

- Identify & Assess

- Evaluate & Respond

- Implement, Monitor & Adjust

Scope & Plan

The first step is to understand the scope of the project. In the case of the CCPA, the scope will relate to all of the processes that touch consumer data, which will help you to identify:

- All of the systems (electronic and otherwise) that may contain consumer data

- All of the people that participate in data-related processes (including management)

- All of the applicable policies and legal documents

Once you have identified all of the elements that you will include for compliance, you can create your project plan:

- Specify a deadline for compliance

- Identify milestones with due dates

- Identify tasks with due dates

- Identify responsible persons and assign them the tasks

With your scope and project plan in hand, you can kick the project off with your team. Pro-tip: Ensure that you have buy-in from your leadership team before launching the compliance project. With their support, you will have the necessary leverage to get tasks completed.

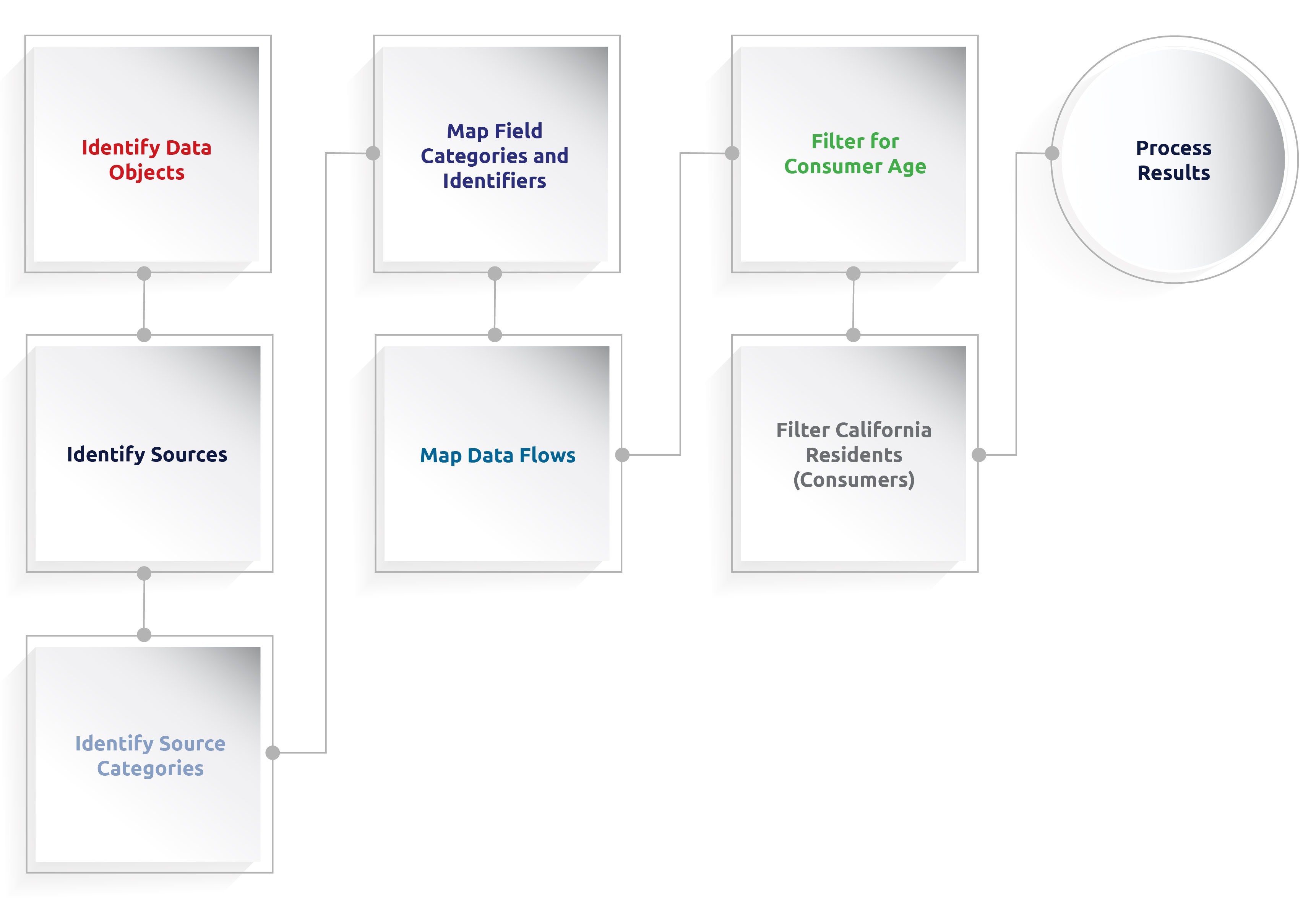

Identify & Assess

The first project phase will relate to identifying the data and how it flows throughout the organization. Consider using a combination of flowcharts and tables (see Chapter 4) to map out the data that will be included for compliance.

Once the data is mapped out you can assess it for risk, specifically as it is used within certain processes. Understanding which sections of data have a higher risk for non-compliance will allow you to prioritize any actions you need to take towards compliance.

Evaluate & Respond

In this phase, you will evaluate your findings to understand the impact. For each finding, you then develop a response, which is typically in the form of a control for specific risks, or a fundamental system or process change where non-compliance is systemic.

Combine your responses into an implementation plan that can be tracked against the project deadline.

Implement, Monitor & Adjust

In this final phase, you implement all the changes required for compliance. However, this is not just a “lock up and go” situation; every implemented change will need some form of monitoring.

It is the result of your monitoring activities that will allow you to make adjustments and improvements.

“You don’t know what you got till it's gone”

Before implementing any changes, you need to know what your data looks like. In this section, we’ll look at the practical steps you’ll need to take to map your data and assess the extent of your CCPA compliance requirements.

California Civil Code 1798.100:

(a) A consumer shall have the right to request that a business that collects a consumer’s personal information disclose to that consumer the categories and specific pieces of personal information the business has collected.

(b) A business that collects a consumer’s personal information shall, at or before the point of collection, inform consumers as to the categories of personal information to be collected and the purposes for which the categories of personal information shall be used. A business shall not collect additional categories of personal information or use personal information collected for additional purposes without providing the consumer with notice consistent with this section.

(c) A business shall provide the information specified in subdivision (a) to a consumer only upon receipt of a verifiable consumer request.

(d) A business that receives a verifiable consumer request from a consumer to access personal information shall promptly take steps to disclose and deliver, free of charge to the consumer, the personal information required by this section. The information may be delivered by mail or electronically, and if provided electronically, the information shall be in a portable and, to the extent technically feasible, in a readily useable format that allows the consumer to transmit this information to another entity without hindrance. A business may provide personal information to a consumer at any time, but shall not be required to provide personal information to a consumer more than twice in a 12-month period.

(e) This section shall not require a business to retain any personal information collected for a single, one-time transaction, if such information is not sold or retained by the business or to reidentify or otherwise link information that is not maintained in a manner that would be considered personal information.

(Amended (as added by Stats. 2018, Ch. 55, Sec. 3) by Stats. 2018, Ch. 735, Sec. 1. (SB 1121) Effective September 23, 2018. Section operative January 1, 2020, pursuant to Section 1798.198.)

Give them what they ask for

The motivation for mapping your data relates to the right the consumer has to ask for disclosure of the data you are collecting, where you are getting it and to whom you are selling it.

Code 1798.110. (a) reads as follows:

A consumer shall have the right to request that a business that collects personal information about the consumer disclose to the consumer the following:

(1) The categories of personal information it has collected about that consumer

(2) The categories of sources from which the personal information is collected.

(3) The business or commercial purpose for collecting or selling personal information.

(4) The categories of third parties with whom the business shares personal information.

(5) The specific pieces of personal information it has collected about that consumer.”

Not only does a map with this profile assist in developing disclosure and deletion processes, but it will also indicate the overall compliance risk your business faces.

CCPA vs GDPR: It’s a matter of scope

The geographic scope of GDPR forced many businesses to take a more blanket approach that would make an initial mapping less practical. Instead, many opted to simply implement the various privacy measures across all their data sets, the geographic origin notwithstanding.

Moreover, the comprehensive nature of GDPR required fundamental changes to systems which would make separate technological standards cumbersome and costly to implement and maintain.

Finally, GDPR compliance surrounds a single data object, namely a ‘data subject’ which is a natural, identifiable person. The CCPA includes both households and devices beyond individuals, which makes data mapping a necessity.

The CCPA is focused solely on Californian consumers and is not prescriptive on how systems must be secured or data should be managed towards data privacy. Instead, it requires specific knowledge of your Californian consumers which makes data mapping more important.

If you haven’t mapped your data for GDPR, this may be a good exercise to understand your greater compliance risk as more regions implement data privacy laws.

Practical steps to take

Identify data objects (residents, households, devices)

The CCPA’s underlying premise is that data on households and devices links back to individual consumers, which makes it personal information by extension.

Consequently, mapping your data will start with mapping the data objects you maintain, specifically individuals, households and devices.

Identify data sources and source categories

Where do you get this data? Typically data can originate from the following, among others:

- Active submission by consumers

- Automated collection by systems (such as web analytics or algorithm-derived data)

- Other forms of observation

- Inferences from existing data

- Acquisition from other businesses or third parties

- Acquisition from public sources (both from government and private sources)

Be as detailed as possible in identifying specific sources that will allow you to identify and map them to categories like the list above.

Map data fields to field categories and identifiers

The CCPA indicates 11 different categories of personal data, including a long list of identifiers that relates to people, households and devices. In this step, map your data fields to these categories and where possible, identifiers.

The categories include:

| Category | Example/Description from Applicable Law |

|---|---|

| Identifiers | Real name, alias, postal address, unique personal identifier, online identifier, Internet Protocol address, email address, account name, social security number, driver’s license number, passport number, or other similar identifiers. |

| Any categories of personal information described in Cal. Civ. Code 1798.80(e) | ‘Personal information’ means any information that identifies, relates to, describes, or is capable of being associated with a particular individual, including, but not limited to, his or her name, signature, social security number, physical characteristics or description, address, telephone number, passport number, driver’s license or state identification card number, insurance policy number, education, employment, employment history, bank account number, credit card number, debit card number, or any other financial information, medical information, or health insurance information. ‘Personal information’ does not include publicly available information that is lawfully made available to the general public from federal, state, or local government records. |

| Characteristics of protected classes |

Protected classes include:

|

| Commercial information | ‘Biometric information’ means an individual’s physiological, biological or behavioral characteristics, including an individual’s deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA), that can be used, singly or in combination with each other or with other identifying data, to establish individual identity. Biometric information includes, but is not limited to, imagery of the iris, retina, fingerprint, face, hand, palm, vein patterns, and voice recordings, from which an identifier template, such as a faceprint, a minutiae template, or a voiceprint, can be extracted, and keystroke patterns or rhythms, gait patterns or rhythms, and sleep, health, or exercise data that contain identifying information. |

| Internet or other electronic network activity information | Including, but not limited to, browsing history, search history, and information regarding a consumer’s interaction with an Internet Web site, application, or advertisement. |

| Geolocation data | Longitude, latitude or any other geographic positional information expressed in any format that can be directly associated with a person, household or device, including graphical maps. |

| Audio, electronic, visual, thermal, olfactory, or similar information |

Voice recordings |

| Professional or employment-related information |

Work History |

| Education information |

Information that is not publicly available personally identifiable information as defined in the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act (20 U.S.C. section 1232g, 34 C.F.R. Part 99) |

| Inferences drawn from any of the information identified in this subdivision to create a profile about a consumer |

Reflecting the consumer’s preferences, characteristics, psychological trends, predispositions, behavior, attitudes, intelligence, abilities, and aptitudes. |

Understand Data Flows

Now that you know where the data comes from and what categories it falls into, you can assess where the data is going. This important step clarifies what data is regarded as being ‘sold’ or ‘disclosed’ as defined by the CCPA:

‘Sell’, ‘selling’, ‘sale’ or ‘sold’ means selling, renting, releasing, disclosing, disseminating, making available, transferring, or otherwise communicating orally, in writing, or by electronic or other means, a consumer’s personal information by the business to another business or a third party for monetary or other valuable consideration.

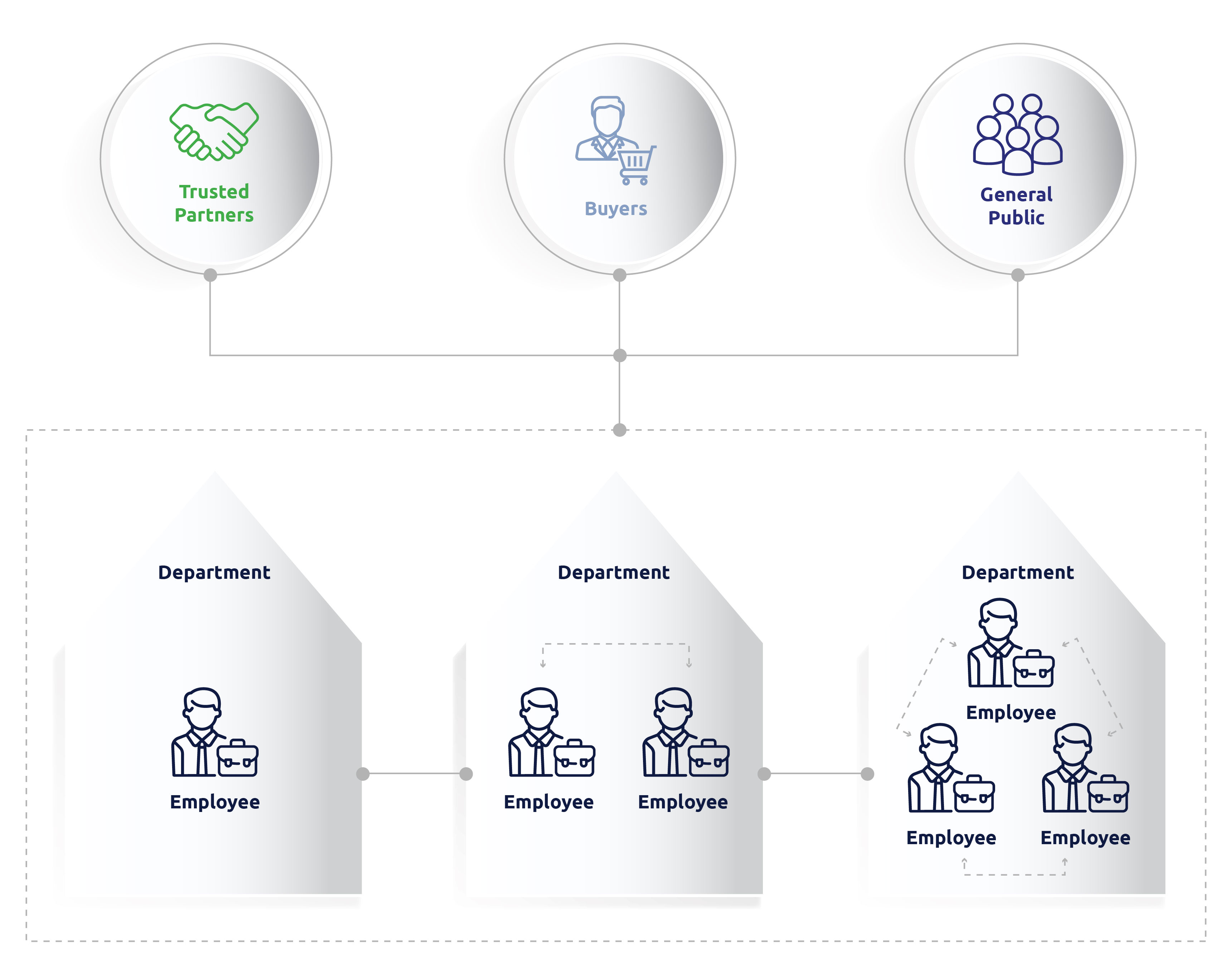

Typically data will be shared:

- Internally between individuals or departments

- Externally with trusted partners

- Externally with buyers

- Externally with the general public

For example, you will collect personal data on your employees, but you won’t share it with buyers or the general public. If you use a third-party payroll system in the cloud then you are sharing it with a trusted vendor, who in turn has a number of obligations to maintain the privacy of the data.

Your end goal is to generate two lists using the categories in the previous step, one with categories that are sold, and one with categories that are disclosed, but not sold, for example:

| Object | Object Description | Category | Status | Recipient | Recipient Category |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Object: Consumer | Object Description: Website Visitor | Category: Internet or other electronic network activity information | Status: Disclosed | Recipient: Google Analytics | Recipient Category: Web Analytics |

| Object: Household | Object Description: Customer Address | Category: Geolocation data | Status: Sold | Recipient: GeoRus | Recipient Category: Client |

| Object: Consumer | Object Description: Employee | Category: Biometric information | Status: Disclosed | Recipient: BioAccess Systems | Recipient Category: Security Vendor |

| Object: Device | Object Description: IP Address | Category: Internet or other electronic network activity information | Status: Disclosed (internal use only) | Recipient: Hubspot | Recipient Category: CRM |

Filter for the age of consumers

Consumer age is important for all pieces of privacy legislation, but specifically so for the CCPA.

In Code 1798.120(c) the issue of age is dealt with as follows:

a business shall not sell the personal information of consumers if the business has actual knowledge that the consumer is less than 16 years of age, unless the consumer, in the case of consumers between 13 and 16 years of age, or the consumer’s parent or guardian, in the case of consumers who are less than 13 years of age, has affirmatively authorized the sale of the consumer’s personal information. A business that willfully disregards the consumer’s age shall be deemed to have had actual knowledge of the consumer’s age. This right may be referred to as the “right to opt-in.

The important implication here is that by ignoring age, and then selling consumer data that may contain children under the age of 16, you are by default contravening the law and may face maximum penalties.

For this reason, when preparing for CCPA compliance you will need a clear classification of your consumer data by age. When filtering for age you will initially have the following brackets:

- Older than 16: consumers in this age bracket have the right to opt out of having their data sold

- Between 13 and 16: consumers in this age bracket must opt into having their information sold

- Below 13: consumers in this age bracket will require a parent or guardian to opt them into having their data sold

- Unknown: if you have age-related data, consumers in this bracket needs to be excluded from any sales until you can confirm their age

Important note: When it comes to age verification it is better to err on the side of caution. Section 1798.100(d) notes that data gathered for a one-time transaction, or data that wouldn’t under normal operating circumstances be maintained, is not required by the CCPA. The possible implication here is that should one not normally maintain age-related information, the CCPA wouldn’t require it. However, the fact that the law emphasizes age verification means that it should be seen as data that must be maintained for the sake of compliance.

Filter for Californian residents (consumers)

With a fully mapped data set, the final step is to filter for Californian residents. Outside of the borders of California, your data might contain website visitors or customers who reside in California.

Filtering for consumers from California can be on the basis of any address records, or on the basis of geolocation or IP location.

Important note regarding employee data: At this time there are still debates as to the extent to which employee data will be subject to the CCPA. Without any amendments, the law extends fully to employees, however, a recently proposed amendment (AB25) will restrict the way in which employee data is managed under the CCPA. Regardless of whether employee data is subject to the CCPA, it is good practice to ensure maximum privacy protection for this type of data.

Your first line of defense

Love them or hate them, legal documents are critical when it comes to compliance. This is one of the first places regulators will look, and they act as a guide to ensure further compliance. More importantly, should your business ever be challenged in court for non-compliance, your legal documents will play an important role in your defense.

More than just a privacy policy

The CCPA makes specific mention of privacy policies and the ways in which they need to reflect information specific to California residents or households in Code 1798.135(a)(2) and (3):

(a) A business that is required to comply with Section 1798.120 shall, in a form that is reasonably accessible to consumers...

(2) Include a description of a consumer’s rights pursuant to Section 1798.120, along with a separate link to the “Do Not Sell My Personal Information” Internet Web page in:

(A) Its online privacy policy or policies if the business has an online privacy policy or policies.

(B) Any California-specific description of consumers’ privacy rights.

(3) Ensure that all individuals responsible for handling consumer inquiries about the business’s privacy practices or the business’s compliance with this title are informed of all requirements in Section 1798.120 and this section and how to direct consumers to exercise their rights under those sections.

CCPA vs GDPR: It’s a matter of detail

GDPR is a more verbose law than that of the CCPA. However, they both require that legal documents of various flavors are updated to include the data privacy rights of the data subject or consumer.

The content of these changes will differ in line with the requirements of the specific law, and in the case of the CCPA, this would be focused on the sale of data and the rights of the consumer to opt out of this process.

Practical steps to take

Privacy policy

The key document that will need your attention is the privacy policy. You can opt for a California-only section or integrate the various parts into your privacy policy as a whole. Some areas to consider include:

- Paragraphs on requesting data disclosure, deleting data and opting out; be sure to include a direct link to the “Do Not Sell My Personal Information” page

- Identifying broad usage categories that personal data falls into

- Identifying third-party categories to whom data may be sold

- Explaining the right and process to opt out of third parties selling the data on

- Including applicable definitions from the CCPA 1798.140

- Indicating applicable exclusions from CCPA 1798.145

- Clearly stating your commitment to data security and explaining the breach procedure

Cookie policy

The changes are not limited to your privacy policy. Presuming that you have a cookie policy in place (which is a good idea for GDPR compliance anyway), this too will need to reflect information on the rights of Californian residents.

Cookies are designed to track behavior on websites, and any data, even the consequent insights associated with the data, is considered personal information within the context of the CCPA. When updating your Cookie Policy, consider adding a specific section for Californian residents.

Employee contracts

You may need to update employee contracts in two different ways:

The first is to include clauses that cover the responsibility of the employee to honor the various data privacy laws with which the company is required to comply. In the contracts itself, these may be broadly stated to include all the relevant laws, but make sure to back it up with proper training on each of the specific regulations. Training or awareness is specifically required by the CCPA and should not be neglected.

Secondly, for companies that operate within the borders of California and have residents as employees or subcontractors, there may be a need to update the relevant employment contracts to indicate the rights afforded to them by the CCPA as it relates to the personal information you collect. You should also consider including the limitations of their rights, for example, they may not be able to request deletion of their data as you are practically and legally obliged to maintain their records to operate.

Important note regarding employee data: At this time there are still debates as to the extent to which employee data will be subject to the CCPA. Without any amendments, the law extends fully to employees, however, a recently proposed amendment (AB25) will restrict the way in which employee data is managed under the CCPA. Regardless of whether employee data is subject to the CCPA, it is good practice to ensure maximum privacy protection for this type of data.

Third-party agreements

Any agreements with third parties may need to be updated to reflect the rights of the Californian consumers that are transferred along with data that is being sold. This should include a notice that third parties may not resell the data they bought without an explicit notice to the consumer, and giving them a clear means to opt out.

If you are collecting consumer data from California-based vendors as part of your operation, you may also need to include some information on their rights as related to the CCPA.

What’s in a name?

The CCPA in its current format is a broad-strokes type of law. Instead of providing detailed definitions for terms, the authors decided to rather apply a single term across a broad range of functions or activities.

A core right given to consumers by the CCPA is that of opting out of the sale of their data, and due to the broad definition for the term ‘sell’, the requirement to review all the processes related thereto is a priority.

Section 1798.125:

(a) (1) A business shall not discriminate against a consumer because the consumer exercised any of the consumer’s rights under this title, including, but not limited to, by:

(A) Denying goods or services to the consumer.

(B) Charging different prices or rates for goods or services, including through the use of discounts or other benefits or imposing penalties.

(C) Providing a different level or quality of goods or services to the consumer.

(D) Suggesting that the consumer will receive a different price or rate for goods or services or a different level or quality of goods or services.

(2) Nothing in this subdivision prohibits a business from charging a consumer a different price or rate, or from providing a different level or quality of goods or services to the consumer, if that difference is reasonably related to the value provided to the consumer by the consumer’s data.

(b) (1) A business may offer financial incentives, including payments to consumers as compensation, for the collection of personal information, the sale of personal information, or the deletion of personal information. A business may also offer a different price, rate, level, or quality of goods or services to the consumer if that price or difference is directly related to the value provided to the consumer by the consumer’s data.

(2) A business that offers any financial incentives pursuant to subdivision (a), shall notify consumers of the financial incentives pursuant to Section 1798.135.

(3) A business may enter a consumer into a financial incentive program only if the consumer gives the business prior opt-in consent pursuant to Section 1798.135 which clearly describes the material terms of the financial incentive program, and which may be revoked by the consumer at any time.

(4) A business shall not use financial incentive practices that are unjust, unreasonable, coercive, or usurious in nature.

Of definition, discrimination and incentives

In Section 1798.140(t)(1), the CCPA states the following:

'Sell’, ‘selling’, ‘sale’ or ‘sold’ means selling, renting, releasing, disclosing, disseminating, making available, transferring, or otherwise communicating orally, in writing, or by electronic or other means, a consumer’s personal information by the business to another business or a third party for monetary or other valuable consideration.

This section provides us with a definition of what the law looks at when it talks about the selling of personal information. Section 1798.125 highlights two aspects of the sales process, namely that businesses can’t discriminate against consumers who exercise their CCPA rights, and that businesses are allowed (within reason) to incentivise data collection.

CCPA vs GDPR: To sell or not to sell – that is the difference

With its focus on general data protection, GDPR makes no direct mention of the sale of data. Instead it focuses on processors and controllers, and giving the data subject the right to opt in to different business activities. This means that the selling of data under GDPR is a matter of proving that the data subject

a) was informed that their data may be sold when they provided it and

b) gave consent that the data may be used for these purposes.

The CCPA places heavy emphasis on the sale of personal information as a specific business function, but generally reflects the idea that the consumer must be informed that their data may be sold. Different to GDPR however, the consumer must be given a clear path to opt out, rather than provide initial consent.

Refine the list

In the first step you mapped your data and ended up with a list that indicates which data objects are sold, and which data is disclosed, but not sold.

Using the definition provided by the CCPA, you can now add additional depth as follows:

| Object | Object Description | Category | Status | Sale Type | Discrimination? | Incentive? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Object: Consumer | Object Description: Product Preferences | Category: Behavioral | Status: Sold | Sale Type: Partner Data Exchange | Discrimination? Yes | Incentive? Yes |

| Object: Household | Object Description: Customer Address | Category: Geolocation Data | Status: Sold | Sale Type: Renting | Discrimination? No | Incentive? No |

During this exercise, you will need to be very honest about the differences in the nature of the product or service that the consumer gets when their personal information is available, versus when they opted out. The law will allow a difference in what you deliver if you can show that the personal information is a necessary component to provide the given enhancements. However, if you can deliver precisely the same product or service regardless of personal information, then by law you will need to do so.

Here you will also have the opportunity to think through any incentives that you may incorporate in your request for personal data. On the one hand you may consider new ways to entice people to provide their personal information, but on the other hand you will need to make sure that any incentives are legally acceptable.

Using the enhanced mapping you can devise strategies for:

- Compliance where discrimination in products or services can’t be justified

- Compliance, and improvements, where incentives apply

Time to do something

With your data properly mapped out and the data sales processes clearly identified, you can implement updated consumer data processes. This is the first practical step towards measurable compliance which means that this part of the project should get adequate attention.

In this chapter we will look at the major consumer processes required by the CCPA, and what it will take to implement them.

Processes to verify, share and delete data

There are two sections of the CCPA that speaks to business processes, namely Sections 1798.130 and 1798.135. What we can deduce from these sections is that the following processes need to be in place:

- Data request (Right to Know) and data portability, including consumer verification and authorization

- Process to opt out of the sale of data (Right to Opt Out)

- Consumer data deletion process, including appropriate decision trees to determine if deletion is warranted and can be executed

- Various notification processes, including breach notifications

- Where applicable, age verification and parental consent

Section 1798.130:

1798.130. (a) In order to comply with Sections 1798.100, 1798.105, 1798.110, 1798.115, and 1798.125, a business shall, in a form that is reasonably accessible to consumers:

(1) Make available to consumers two or more designated methods for submitting requests for information required to be disclosed pursuant to Sections 1798.110 and 1798.115, including, at a minimum, a toll-free telephone number, and if the business maintains an Internet Web site, a Web site address.

(2) Disclose and deliver the required information to a consumer free of charge within 45 days of receiving a verifiable consumer request from the consumer. The business shall promptly take steps to determine whether the request is a verifiable consumer request, but this shall not extend the business’s duty to disclose and deliver the information within 45 days of receipt of the consumer’s request. The time period to provide the required information may be extended once by an additional 45 days when reasonably necessary, provided the consumer is provided notice of the extension within the first 45-day period. The disclosure shall cover the 12-month period preceding the business’s receipt of the verifiable consumer request and shall be made in writing and delivered through the consumer’s account with the business, if the consumer maintains an account with the business, or by mail or electronically at the consumer’s option if the consumer does not maintain an account with the business, in a readily useable format that allows the consumer to transmit this information from one entity to another entity without hindrance. The business shall not require the consumer to create an account with the business in order to make a verifiable consumer request.

(3) For purposes of subdivision (b) of Section 1798.110:

(A) To identify the consumer, associate the information provided by the consumer in the verifiable consumer request to any personal information previously collected by the business about the consumer.

(B) Identify by category or categories the personal information collected about the consumer in the preceding 12 months by reference to the enumerated category or categories in subdivision (c) that most closely describes the personal information collected.

(4) For purposes of subdivision (b) of Section 1798.115:

(A) Identify the consumer and associate the information provided by the consumer in the verifiable consumer request to any personal information previously collected by the business about the consumer.

(B) Identify by category or categories the personal information of the consumer that the business sold in the preceding 12 months by reference to the enumerated category in subdivision (c) that most closely describes the personal information, and provide the categories of third parties to whom the consumer’s personal information was sold in the preceding 12 months by reference to the enumerated category or categories in subdivision (c) that most closely describes the personal information sold. The business shall disclose the information in a list that is separate from a list generated for the purposes of subparagraph (C).

(C) Identify by category or categories the personal information of the consumer that the business disclosed for a business purpose in the preceding 12 months by reference to the enumerated category or categories in subdivision (c) that most closely describes the personal information, and provide the categories of third parties to whom the consumer’s personal information was disclosed for a business purpose in the preceding 12 months by reference to the enumerated category or categories in subdivision (c) that most closely describes the personal information disclosed. The business shall disclose the information in a list that is separate from a list generated for the purposes of subparagraph (B).

(5) Disclose the following information in its online privacy policy or policies if the business has an online privacy policy or policies and in any California-specific description of consumers’ privacy rights, or if the business does not maintain those policies, on its Internet Web site, and update that information at least once every 12 months:

(A) A description of a consumer’s rights pursuant to Sections 1798.110, 1798.115, and 1798.125 and one or more designated methods for submitting requests.

(B) For purposes of subdivision (c) of Section 1798.110, a list of the categories of personal information it has collected about consumers in the preceding 12 months by reference to the enumerated category or categories in subdivision (c) that most closely describe the personal information collected.

(C) For purposes of paragraphs (1) and (2) of subdivision (c) of Section 1798.115, two separate lists:

(i) A list of the categories of personal information it has sold about consumers in the preceding 12 months by reference to the enumerated category or categories in subdivision (c) that most closely describe the personal information sold, or if the business has not sold consumers’ personal information in the preceding 12 months, the business shall disclose that fact.

(ii) A list of the categories of personal information it has disclosed about consumers for a business purpose in the preceding 12 months by reference to the enumerated category in subdivision (c) that most closely describe the personal information disclosed, or if the business has not disclosed consumers’ personal information for a business purpose in the preceding 12 months, the business shall disclose that fact.

(6) Ensure that all individuals responsible for handling consumer inquiries about the business’s privacy practices or the business’s compliance with this title are informed of all requirements in Sections 1798.110, 1798.115, 1798.125, and this section, and how to direct consumers to exercise their rights under those sections.

(7) Use any personal information collected from the consumer in connection with the business’s verification of the consumer’s request solely for the purposes of verification.

(b) A business is not obligated to provide the information required by Sections 1798.110 and 1798.115 to the same consumer more than twice in a 12-month period.

(c) The categories of personal information required to be disclosed pursuant to Sections 1798.110 and 1798.115 shall follow the definition of personal information in Section 1798.140.

Section 1798.135:

1798.135. (a) A business that is required to comply with Section 1798.120 shall, in a form that is reasonably accessible to consumers:

(1) Provide a clear and conspicuous link on the business’s Internet homepage, titled “Do Not Sell My Personal Information,” to an Internet Web page that enables a consumer, or a person authorized by the consumer, to opt-out of the sale of the consumer’s personal information. A business shall not require a consumer to create an account in order to direct the business not to sell the consumer’s personal information.

(2) Include a description of a consumer’s rights pursuant to Section 1798.120, along with a separate link to the “Do Not Sell My Personal Information” Internet Web page in:

(A) Its online privacy policy or policies if the business has an online privacy policy or policies.

(B) Any California-specific description of consumers’ privacy rights.

(3) Ensure that all individuals responsible for handling consumer inquiries about the business’s privacy practices or the business’s compliance with this title are informed of all requirements in Section 1798.120 and this section and how to direct consumers to exercise their rights under those sections.

(4) For consumers who exercise their right to opt-out of the sale of their personal information, refrain from selling personal information collected by the business about the consumer.

(5) For a consumer who has opted-out of the sale of the consumer’s personal information, respect the consumer’s decision to opt-out for at least 12 months before requesting that the consumer authorize the sale of the consumer’s personal information.

(6) Use any personal information collected from the consumer in connection with the submission of the consumer’s opt-out request solely for the purposes of complying with the opt-out request.

(b) Nothing in this title shall be construed to require a business to comply with the title by including the required links and text on the homepage that the business makes available to the public generally, if the business maintains a separate and additional homepage that is dedicated to California consumers and that includes the required links and text, and the business takes reasonable steps to ensure that California consumers are directed to the homepage for California consumers and not the homepage made available to the public generally.

(c) A consumer may authorize another person solely to opt-out of the sale of the consumer’s personal information on the consumer’s behalf, and a business shall comply with an opt-out request received from a person authorized by the consumer to act on the consumer’s behalf, pursuant to regulations adopted by the Attorney General.

CCPA vs GDPR: One critical difference

GDPR is explicit about the need for data subject processes, which makes it very similar to the CCPA:

- Data subjects have the right to request their information from processors and controllers

- They have the “Right to be Forgotten” (have their data removed) under specific circumstances

- Notifications are required for breaches and critical changes to the data processing systems of procedures

- Age verification is required given certain circumstances

The critical difference between GDPR and the CCPA is that of opting out versus opting in. Where the CCPA requires a business to establish an opt-out process only for the sale of data, GDPR requires an explicit opt-in process, not just for processing of data, but also for different types of communications. This makes the GDPR more complex to implement and, at face value, more restrictive in the ways that data can be used.

Getting the processes right

Data request and data portability

The CCPA allows consumers to request a report on the data you hold and sell. Before you divulge this information, however, you must be able to positively verify the identity of the consumer and match them to the data on your system. As a first step you should plan and implement such a verification process.

As a general rule, compliance is determined by the extent to which an auditor can find proof that you did whatever the law requires. When it comes to the verification process, keep in mind that logging of the steps within the data request process will allow you to show auditors how you verified such consumer identities. If your process isn’t secure enough, you may have false positives and divulge personal information without consent. But if your process is too controlled it may block legitimate requests and possibly require excessive resources to perform what ought to be a relatively simple task.

Be sure to align your process with the requirements of the law. It must be delivered free of charge, and where possible within a 45-day period. There is some leeway regarding both points, but getting this right will be the first step to practical compliance. Also note that at a minimum you need a toll-free number and a website link as channels through which such requests can take place.

Opt-out processes

A primary purpose of the CCPA is to provide consumers with a way to opt out of the sale of their information. As a result, there must be a supporting process for consumers to opt out of any processes that constitute ‘selling’ their information.

Opt-out processes require positive verification either of the consumer submitting the request, or of the authority given to the person who is opting out on behalf of a consumer.

Data of consumers who opted out must then be excluded from any activity that the law defines as ‘selling’ (See Chapter 6).

Deletion requests

As with data and opt-out requests, deletion requests require positive verification of the consumer submitting the request.

Different to other processes, however, the deletion process must consider the purpose of the data and whether or not the request to delete it is legitimate. For example, if an employee requests that you delete their information, that would impede on your ability to process their salaries. The CCPA allows you to then retain their information because it is an integral part of your business operations.

Once the verification is successful and the data is found not to be required for your business to operate or fulfill its function, you should delete the information.

Notification processes

The CCPA wants to ensure that consumers remain informed about what you are doing with their data. You will need to provide notifications in the following situations:

- On collection of their data regarding the categories of data you are collecting, and the purpose for which you are collecting the information. This may also be a notification displayed at the collection point, such as a clearly visible paragraph underneath a web form.

- On selling the data to a third party who will be reselling the data. Consumers need to get the opportunity to opt out of the secondary sale of their data by the third party.

- On offering financial incentives related to the acquisition of consumer data.

- On the extension of the 45-day deadline for the provision of data, explaining the reason why the request for data could not be completed within the allotted period.

- On the transfer of consumer data as an asset during a business merger or acquisition.

- When the new owner of the data assets intend to change the way in which the data will be used (related to the previous point).

- When a data breach occurs.

- When refusing requests by consumers, such as in the case of excessive or unfounded requests for data.

A good rule of thumb is to make sure that any notices are clear and easily accessible, and provide the consumer with a way to respond, especially in those cases where they need a way to opt out.

Age verification and parental consent

In Chapter 4, we touched on the issue of age verification. The CCPA states that you wouldn’t need to gather data that you wouldn’t normally gather in an effort to become compliant. However, the law also states that there can be severe penalties for selling data for consumers under the age of 18, where opt-in is required.

It is better to err on the side of caution if you are likely to store the data of younger consumers. Age confirmation and opt-in are required below the age of 18, and parental consent below the age of 13, specifically for the sale of data.

Systems are process tools

Whenever a process changes, the system must follow, otherwise you would never achieve the expected results. So in that way a system is a reflection of the process, or a process tool. In this chapter we look at the fundamental changes that a system needs to improve compliance.

Relevant sections from the law

Sections 1798.115 and 1798.120 should be read in conjunction with Sections 1798.130 and 1798.135 in Chapter 7. The essence of the sections is that the consumer has the right to request a report on their data, and be given the opportunity to opt out of the sale thereof, among other things. In the previous chapter we looked at the processes that would be required for compliance, and in this chapter we will apply those processes to typical systems.

These are the processes and their related systems that will require updating:

| Process | Systems |

|---|---|

| Data request and portability |

|

| Opt-out of sales of data |

|

| Consumer data deletion |

|

| Notifications |

|

| Age verification |

|

Section 1798.115:

1798.115. (a) A consumer shall have the right to request that a business that sells the consumer’s personal information, or that discloses it for a business purpose, disclose to that consumer:

(1) The categories of personal information that the business collected about the consumer.

(2) The categories of personal information that the business sold about the consumer and the categories of third parties to whom the personal information was sold, by category or categories of personal information for each third party to whom the personal information was sold.

(3) The categories of personal information that the business disclosed about the consumer for a business purpose.

(b) A business that sells personal information about a consumer, or that discloses a consumer’s personal information for a business purpose, shall disclose, pursuant to paragraph (4) of subdivision (a) of Section 1798.130, the information specified in subdivision (a) to the consumer upon receipt of a verifiable consumer request from the consumer.

(c) A business that sells consumers’ personal information, or that discloses consumers’ personal information for a business purpose, shall disclose, pursuant to subparagraph (C) of paragraph (5) of subdivision (a) of Section 1798.130:

(1) The category or categories of consumers’ personal information it has sold, or if the business has not sold consumers’ personal information, it shall disclose that fact.

(2) The category or categories of consumers’ personal information it has disclosed for a business purpose, or if the business has not disclosed the consumers’ personal information for a business purpose, it shall disclose that fact.

(d) A third party shall not sell personal information about a consumer that has been sold to the third party by a business unless the consumer has received explicit notice and is provided an opportunity to exercise the right to opt-out pursuant to Section 1798.120.

1798.120. (a) A consumer shall have the right, at any time, to direct a business that sells personal information about the consumer to third parties not to sell the consumer’s personal information. This right may be referred to as the right to opt-out.

(b) A business that sells consumers’ personal information to third parties shall provide notice to consumers, pursuant to subdivision (a) of Section 1798.135, that this information may be sold and that consumers have the “right to opt-out” of the sale of their personal information.

(c) Notwithstanding subdivision (a), a business shall not sell the personal information of consumers if the business has actual knowledge that the consumer is less than 16 years of age, unless the consumer, in the case of consumers between 13 and 16 years of age, or the consumer’s parent or guardian, in the case of consumers who are less than 13 years of age, has affirmatively authorized the sale of the consumer’s personal information. A business that willfully disregards the consumer’s age shall be deemed to have had actual knowledge of the consumer’s age. This right may be referred to as the “right to opt-in.”

(d) A business that has received direction from a consumer not to sell the consumer’s personal information or, in the case of a minor consumer’s personal information has not received consent to sell the minor consumer’s personal information shall be prohibited, pursuant to paragraph (4) of subdivision (a) of Section 1798.135, from selling the consumer’s personal information after its receipt of the consumer’s direction, unless the consumer subsequently provides express authorization for the sale of the consumer’s personal information.

Section 1798.120:

1798.120. (a) A consumer shall have the right, at any time, to direct a business that sells personal information about the consumer to third parties not to sell the consumer’s personal information. This right may be referred to as the right to opt-out.

(b) A business that sells consumers’ personal information to third parties shall provide notice to consumers, pursuant to subdivision (a) of Section 1798.135, that this information may be sold and that consumers have the “right to opt-out” of the sale of their personal information.

(c) Notwithstanding subdivision (a), a business shall not sell the personal information of consumers if the business has actual knowledge that the consumer is less than 16 years of age, unless the consumer, in the case of consumers between 13 and 16 years of age, or the consumer’s parent or guardian, in the case of consumers who are less than 13 years of age, has affirmatively authorized the sale of the consumer’s personal information. A business that willfully disregards the consumer’s age shall be deemed to have had actual knowledge of the consumer’s age. This right may be referred to as the “right to opt-in.”

(d) A business that has received direction from a consumer not to sell the consumer’s personal information or, in the case of a minor consumer’s personal information has not received consent to sell the minor consumer’s personal information shall be prohibited, pursuant to paragraph (4) of subdivision (a) of Section 1798.135, from selling the consumer’s personal information after its receipt of the consumer’s direction, unless the consumer subsequently provides express authorization for the sale of the consumer’s personal information.

(Amended (as added by Stats. 2018, Ch. 55, Sec. 3) by Stats. 2018, Ch. 735, Sec. 5. (SB 1121) Effective September 23, 2018. Section operative January 1, 2020, pursuant to Section 1798.198.)

CCPA vs GDPR: Think like an auditor

With both the CCPA and GDPR, the key is to set up your systems so that there is a clear and unambiguous audit trail. Every action taken on the system must be recorded, or you must retain some form of proof that actions were completed, or were not completed as they were otherwise interrupted. GDPR requires that systems do what the law requires, and the proof sits with auditable log files and system reports.

Four quick wins

Due to the variability of the systems out there, this guide can’t share all the changes that need to be implemented. But there are a number of quick wins that any team can take to get on the road to compliance.

Quick Win 1: Add “Do not sell my personal information” link to the website

One of the first, and most visible, changes that you can make is to add a link on your website that allows consumers to opt out of the sale of data. In the CCPA, this is known as the “Do not sell my personal information” link.

The link should lead consumers to a web page that provides a toll-free number for consumers to opt out of the sale of their information. The page should also provide a way for consumers to submit an opt-out request by completing a form or by an appropriate alternative electronic way.

Keep in mind that you will need to be able to manage these opt-out requests on your system. Normally this entails the addition of an opt-out field on a database that can be checked automatically or manually by your support staff.

Quick Win 2: Implement updated policies on the website

Include a section in your privacy policies that specifically deals with the CCPA. In this section you should make note of the rights of the consumer in California, as well as the processes by which consumers can exercise those rights on your website. You should include a link in this section to the “Do not sell my private information” page.

It is also a good idea to include timeframes for handling data requests, and indicate any costs that may be incurred for requests that exceed the annual limits of free requests set by the CCPA.

Quick Win 3: Mask data where applicable

Masking data is a powerful way to ensure that data is secure in certain circumstances. Data masking is effective because it decreases the value of data to intruders, and ensures that any data breaches have a smaller potential footprint for damage.

This is particularly important in test environments where developers have full system access, but data may not be as secure as within a production environment. Masking data allows developers to work with full data-sets without the risk of exposing personal information.

Quick Win 4: Apply encryption